The Federal Reserve’s discount rate is the interest rate that Federal Reserve banks charge commercial banks and other depository institutions when they borrow from the Fed at its discount window. This discount rate is distinct from the discount rate used by financial analysts to calculate the net present value of an investment.

Banks with excess reserves lend to those short on funds to earn interest. The federal funds rate is the Federal Reserve’s target rate for these short-term (typically overnight) interbank loans. The Fed adjusts this rate using open market operations.

But what if banks refuse to lend to a particular bank? In such cases, that bank can turn to the Fed’s discount window, borrowing directly from the Federal Reserve to increase its liquidity and reduce the risk of failing to meet depositor obligations. However, banks typically avoid this option because the discount rate is higher than the federal funds rate, making it a more expensive borrowing option.

Imagine you manage Cloudy Bank and are concerned that major depositors will withdraw their money after you release some unfavorable financial statements. You would like to borrow from Windy Bank, which has excess reserves, to increase your reserves and liquidity. Windy Bank would generally agree, as it can earn interest on the loan. However, Cloudy Bank is in financial trouble, and other banks fear it may default. If no bank is willing to lend, where do you turn?

You go to your local Federal Reserve Bank and borrow from the discount window. The discount rate is the interest rate the Fed charges commercial banks and other depository institutions. These loans require collateral, typically U.S. Treasury bonds or other government securities.

The Fed sets the discount rate higher than the federal funds rate to discourage over-reliance on the discount window. Banks are expected to seek funding from the interbank market first, using the Fed as a lender of last resort.

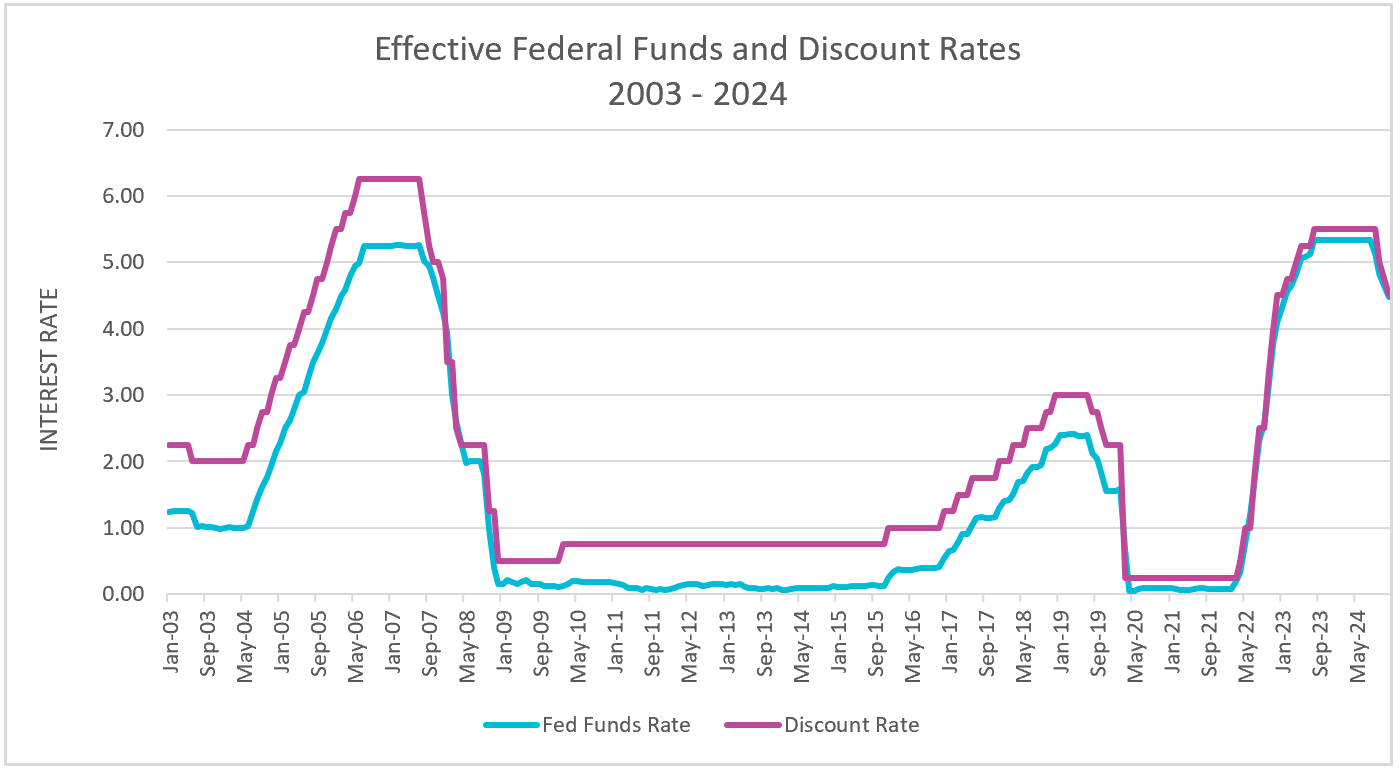

The graph below illustrates the relationship between the discount and federal funds rates since 2003.

Source: Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve uses the discount rate as a tool to manage the economy. During periods of inflation, the Fed raises the discount rate to increase borrowing costs, slow aggregate demand, and reduce business investment. Conversely, it is lowered to stimulate economic growth.

Between 2001 and 2007, the U.S. economy expanded, except for a brief downturn after 9/11. Inflation remained moderate in the early years but began rising in 2004 and 2005. In response, the Fed increased the discount rate in July 2004 after inflation exceeded 3% for three consecutive months. Policymakers continued raising rates gradually until June 2006, when the discount rate peaked at 6.25%.

By 2006, economic growth had slowed, and in Q3, real GDP (RGDP) grew by less than 1%. Weaknesses, particularly in the housing market, became apparent. In August 2007, the Fed began cutting the discount rate. However, concerns about high inflation (above the Fed’s 2% target) delayed aggressive action.

Then, the financial crisis hit. The mortgage industry collapsed, and several major financial institutions failed:

To stabilize the banking system, the Fed slashed the discount rate from 2.25% to 1.25% in one month. By the end of 2008, it had fallen to 0.50%.

Between 2009 and 2016, the U.S. economy grew steadily, but inflation remained low—at times near zero. Some economists feared deflation, while others worried that low interest rates would limit the Fed’s ability to respond to future recessions.

In 2016, the Fed gradually increased the discount rate to prevent overheating and ensure it had room to cut rates in a downturn. By the end of 2018, the discount rate had risen to 3.0%.

Then, in December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. At the time, the discount rate was 2.25%, but policymakers anticipated a severe recession—or even a depression. Congress provided financial relief to households while the Fed slashed rates. Within two months, the discount rate dropped from 2.25% to 0.25%, preventing a deep recession. A severe recession was averted. However, inflation soon followed.

Government stimulus increased aggregate demand, while supply chain disruptions led to higher costs and rising prices. Initially, the Fed expected inflation to subside once supply constraints eased. However, labor shortages and pent-up demand persisted, fueling price increases.

By June 2022, inflation (measured by the Consumer Price Index) hit 9.1%, prompting the Fed to take aggressive action:

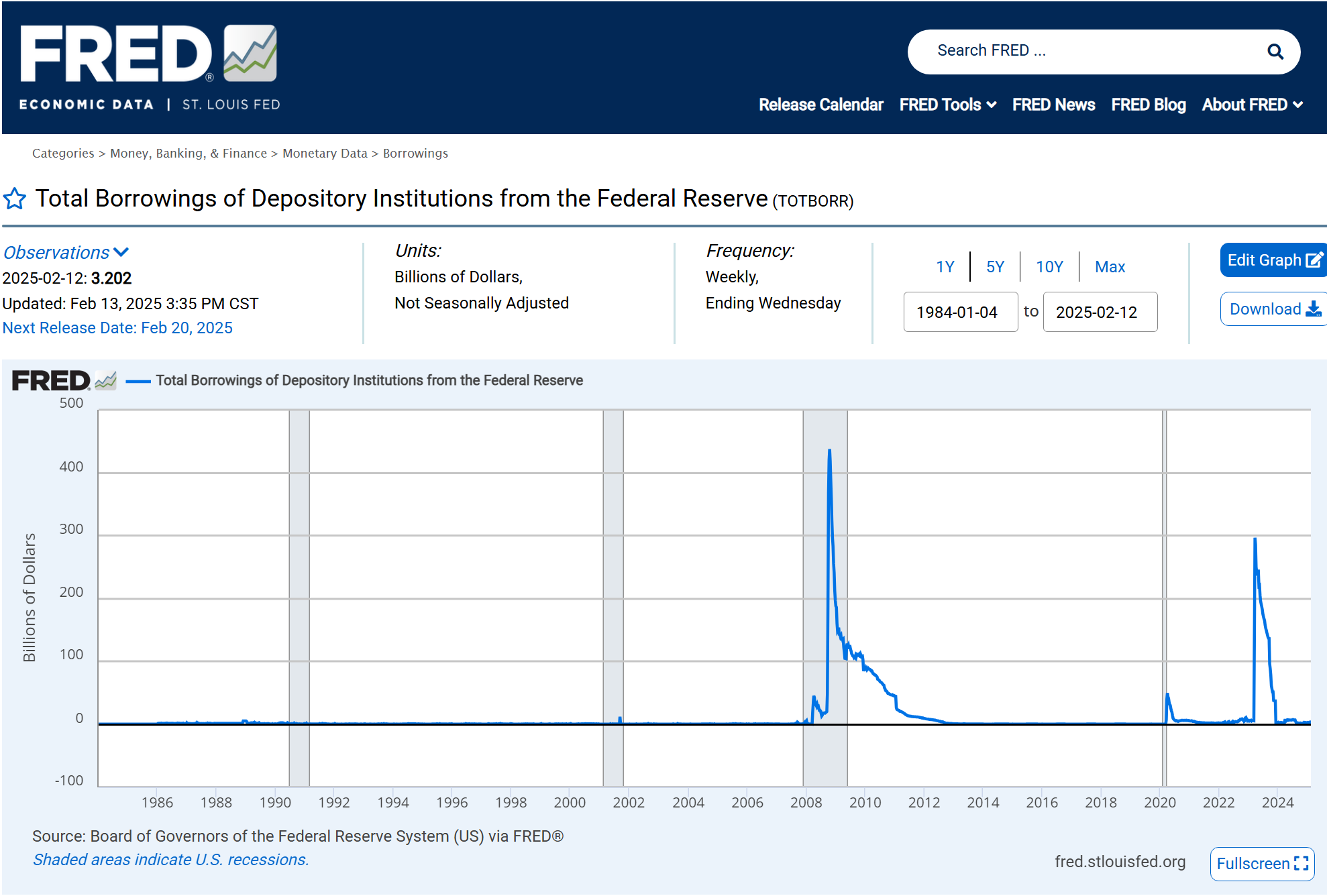

During financial crises, borrowing from the Federal Reserve spikes as banks seek liquidity that is more difficult to secure from other banks that are hoarding their reserves. This was evident after the 2008 financial crisis when institutions such as Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and AIG faced collapse.

Another borrowing surge occurred in March 2023 following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Silvergate Bank. Each institution faced massive withdrawals, shaking confidence in the banking system. Fearing similar runs, other banks borrowed from the Fed to bolster reserves.

Financial analysts use a discount rate to assess the value of an investment. Since money today is worth more than the same amount in the future—due to inflation and opportunity costs—analysts apply a discount rate to estimate the present value of future cash flows. The choice of a discount rate depends on factors such as valuation purpose, opportunity cost, risk level, and cash flow type.

When analyzing an investment, the discount rate represents the minimum acceptable return a company requires to justify the investment. It is used to discount future cash flows and determine their present value.

Consider a forestry company planning to harvest timber in 30 years. Timber investments present unique challenges because they take decades to generate income. For instance, $100,000 in revenues from harvesting timber in 30 years is worth significantly less than $100,000 today. Additionally, companies must continuously invest in managing the timber stand before the final harvest. Analysts discount future cash flows to calculate their net present value and evaluate this investment using an appropriate discount rate.

In bond valuation, discount rates help determine the present value of future interest payments (coupons) and the final principal repayment. A bond’s price is the sum of these discounted future payments, reflecting the time value of money.

Monetary Policy – The Power of an Interest Rate

What is Money

Fractional Reserve Banking and The Creation of Money